At first glance, Joy Drury Cox’s work could be perceived as thoughtful, quiet and unobtrusive. It is in these subtle qualities the viewer is drawn inward, to examine notions of labor, concepts of form, space and constructions within other entities, among other fruitful considerations. Dispelling the engrained mythologies of artists and their methodologies is no easy task. Joy’s work opens these lines of communication by highlighting the simple qualities in good materials and here, explains her aptitude for the succinct by elaborating on her art through action processes.

The reoccurring theme of art through action, a minimalism meets poetry, seems to string through the wide variety of mediums you take on in your work. Where would you say your inspiration stems from? And can you describe your artistic processes in relation to time, materials, your preferred work environment?

Joy Drury Cox (JDC): I like your mention of “art through action.” This is important to me in the most elemental of ways. Like many artists who use more than one medium, it is challenging at times to talk about my work because fundamentally people want to know what I do, what the work looks like.

© Untitled Spaces, Inkjet photograph, dimensions variable, 2006 - present

Saying that I make drawings or take pictures just never feels like enough. I am trying to be intensely cautious when deciding what medium to use to execute each project. Inspiration has always had for me a funny sort of artist-genius mythology tied to it, that at times feels too proprietary and ambiguous. My work stems from actual interactions/reactions to things in the world that anyone and everyone could have a reaction to. It usually starts with the question “why is this thing, this way?” I tend to hold ideas for a while until I have the time to execute them. I usually gravitate to everyday materials- standard sizes, good quality but not overly expensive paper, things you can find at the hardware store. My hope is that these materials are re-highlighted for their simple intrinsic qualities through my work. In grad school when my work became less photographic, I started working at home, and it has been that way for me ever since.

In your statement, you speak to “notions of labor, form and space.” What about these topics creates the most interest for you?

JDC: Obviously these are pretty broad terms, which people have written book lengths worth of research on. My sort of rebirth as an artist came with a series of drawings I did in 2006 of job applications for low-wage service industry jobs. The words labor, form and space have come to take on various meanings in later work, but for that first series, ‘Applications’, I was really interested in the “space” of a form. More specifically, I was thinking about how people might limit or define themselves in a given proscribed space for the purpose of acquiring a job, and whether this standardized evaluation form could accurately reflect how good a job one might do.

© Applications, graphite on paper, 30 in. x 22 in., 2006

The drawings were made by measuring each line/box of the form and then redrawing it on another piece of paper. I omitted the text of the forms, so the viewer was confronted with this pseudo-abstraction. It was a labored process, but one that didn’t have the look of taking a long time, which I liked.

There’s almost an inescapable candor and humility to your work. In other words, in a world increasingly relying on the obscurity in approach, your work though feels a bit more friendly. A great example is your ‘Thank You Letters’. Is there something in particular from your life experiences, environment or anything else that might be contributing to this?

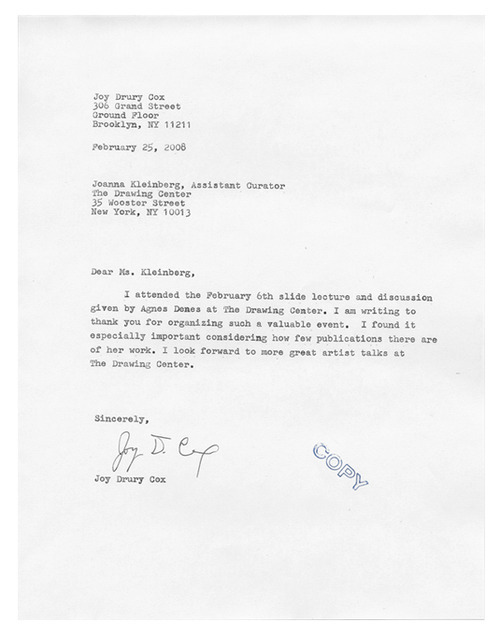

JDC: I have a personal interest in saying thank you. Maybe it has something to do with being raised in the South. The ‘Thank You Letters’ are less these days, but I initially sent them in response to specific works of art that I saw museums and curators choosing to display. The lines of communication among the various strata of artists, curators, gallerists, and museum officials aren’t always so open. A few years ago, I was especially responding to works that I saw in institutional spaces that didn’t seem like the fad of the moment. Obviously, I think artists should be thanked for making the work they do, but I also feel like when an institution displays something risky or unpopular, there should be some sort of acknowledgement from the community as well.

© Thank You Letter, (To Ms. Kleinberg), photocopy w/ stamp 11 x 8.5 inches, 2008

Clearly the letters have an affinity to conceptual art’s aesthetic. I’m using an old Smith Corona typewriter, and it is pretty amazing how many times I had to retype each letter to get a mistake free copy. The process makes me really carefully consider each word and sentence. I hope these letters pick up on some untapped, friendly form of institutional critique as well.

At the same time, there’s a sense of detachment or perhaps an extreme distilling of content, thought and meaning. Are your works of a personal or non-personal nature? Or perhaps more of a social or slightly scientific exploration of labor, form or space?

JDC: My feeling is that most artwork is personal in some general way, if only in that at the very least an artist feels personally connected to an idea that he or she uses art to express. Often the notion of personal or not is made manifest by the conversation surrounding the art rather than the actual objects.

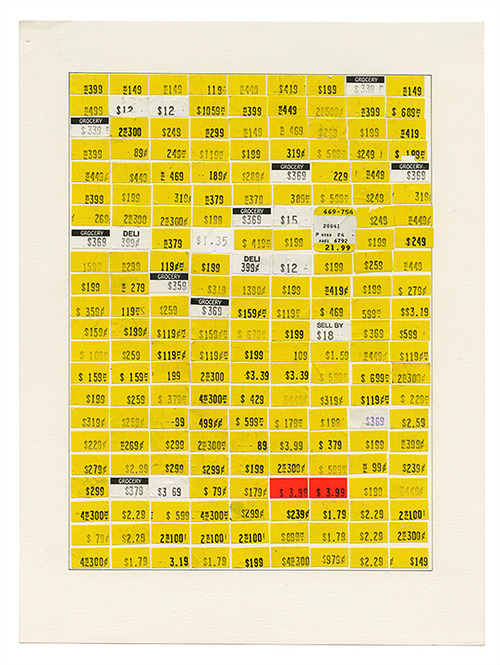

© Subsidy Opportunity #3 ($642.48)

The danger with discussing work in terms of the personal is how quickly the conversation can change to being more about the person and less about the ideas/art object(s). With that, I’m personally invested in the ideas my work deals with, but I am less interested in how these ideas pertain to me specifically.

‘One Liner’ seems to have had a sense of humor instilled in the piece. It appears as if you leave your artistic intention wide open to interpretation by the viewer. Can you speak more on this?

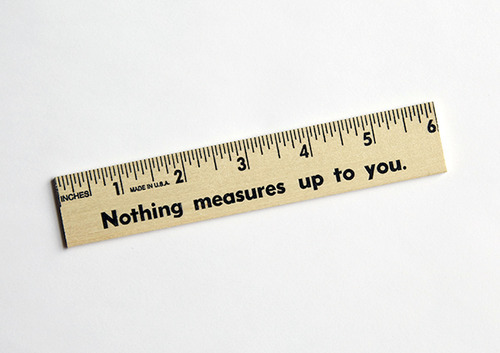

JDC: Measurement has been a component of my work for several years now. I like to address the problems of measurement both through the subject matter that I chose but also through how the work is made (i.e. measuring and re-drawing to scale job applications, birth certificates and other bureaucratic forms). This piece, “one-liner”, was initially conceived of as a response to a call for artists to try to conceive of how cities (like New York) could be in general better places to live. The ruler was supposed to be a pocket-sized tool for people to measure small things in their lives: a device to understand space on a micro level. I guess in some ways I wanted the text to remind the users of how very rare it is to be surrounded by a space where you and all your belongings fit.

© One-liner, wooden ruler, 1 in. x 6 in. edition of 200, signed and numbered, 2011

One of New York’s never ending challenges is coping with or overcoming the inadequacies of confined spaces. Obviously, there is a whole other reading of the piece that is perhaps more where the title comes from. At some point, there will be a twelve-inch ruler and also other rulers made of different materials. I like that the phrase can have more or less weight depending on the ruler. David B. Smith wrote a lovely bit about the piece here.

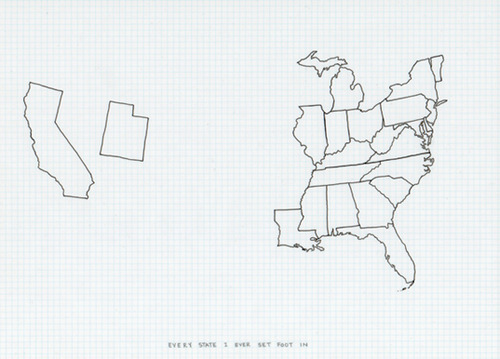

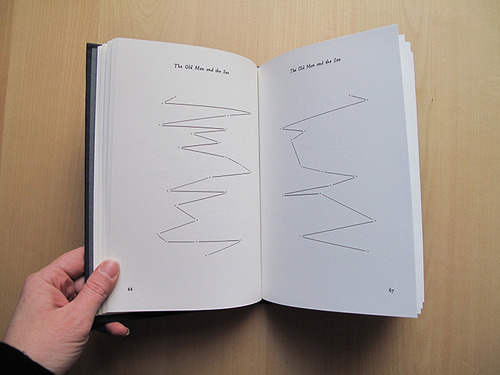

Texts and generally recognized forms take on new meaning in your work. How would you relate your ‘Every State I’ve Ever Stepped Foot’ to ‘Old Man and Sea?

JDC: These two pieces were generated from a similar tactic, which I’ve used in several works. I think standard formats provide viewers with something they are visually comfortable with looking at. Through a subtraction of some information, I hope to destabilize the assumptions that go hand in hand with looking at something recognizable.

© Every State I Ever Set Foot In, 10.5 x 7.5 inches, ink on mylar, 2007

With an “edited” re-presentation of a map or a book, I hope that viewers question the essential nature and boundaries of each. What I loved about each of these pieces was how simple the idea was and how much became open from just carrying it out. With the map, the delineating language, which on the surface reads so clearly, really made me question what it meant to “set foot” somewhere. I was drawing this type of personal map for friends for a while, and I repeatedly got the question, “does it count if I just went to the airport in ______?” I also liked the temporal permanence of the drawing, which is now no longer quite as “true,” which points nicely back to actual functional maps of the world that become outdated.

© Old Man and Sea, ink on mylar and limited edition artist book, dimensions variable, 2006, 20012. Installation view of original ink on mylar drawings.

© In 2012, Conveyor published a limited edition artist book based on the original drawings. The book is available for purchase through Conveyor and Sternthal Books.

Artists are always working up something new. Do you see yourself taking your work in a new direction, implementing any new mediums or installation techniques that you’d like to share?

JDC: I am an artist. Things are always simmering…

---

LINKS

Joy Drury Cox

United States

share this page