Your work speaks about the socio economic and political forces that shape our landscape. Could you talk about the evolution of your thinking that led to this line of inquiry?

Jeff Brouws (JB): I’ve been actively photographing the American cultural Landscape for about 25 years. Initially what I examined were the older elements of roadside culture — what Walker Evans called the “historical contemporary.” At the outset I was on a Road Trip — this was a purely visually engagement: I saw something that attracted me and made a photograph. Yes … I could be in Shamrock, Texas on Route 66, or on Highway 99 in Bakersfield, California, and see the freeway about a quarter mile away in the distance and understand that its presence had displaced whole economies and lifestyles. However, being self-taught and not emerging from an academic environment where I might have learned an interdisciplinary approach to the subject matter, I accentuated the visual, content in the role of photographer. Then two pivotal people came into my life in the early 1990s and opened me up to broader possibilities. I had been in contact with George Thompson at The Center for American Places about a possible book project for their Creating the North American Landscape series. While that project never materialized we had an engaging, supportive correspondence. He urged me to start reading into cultural geography texts to supplement the image making. During this phase I began to fully mine the available literature across the cultural geography spectrum, reading into the works of J. B Jackson, John Stilgoe and others. The lucid content of Jackson’s and Stilgoe’s essays was “a conversion experience to a new way of looking at the built environment”.

At the same time I had a girlfriend who was immersing herself in the french deconstructionists while at UC Santa Cruz, and while that material was intellectually challenging and way over my head, I did read a little Baudrillard. A decade later I started perusing the work of Henri Lefebvre, Marc Auge and some of the other social theorist who viewed everything through the prism of political economy, analyzing the structures, spaces (and places) and the systems that shape our lives and our landscapes. These were some of the same questions my girlfriend would put to me about highway environments I was shooting: why is it the way that it is? What factors created it, where did it come from, how did it develop? I also read books by Dolores Hayden explaining how different landscapes could have divergent histories depending on what gender, economic or racial class you were talking to. In short I began to see that photography (and being a photographer) had myriad components that impacted the work — that photography could be about anthropology, economics, history or sociological issues. I have to say however: once you start deploying this line of questioning it’s hard to ever look at the world in the same fashion. It reminds me of those Question Authority bumper stickers we all use to see. Every landscape has something unique to impart about social realities once you decide to inquire.

That same girlfriend also gave me a copy of Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour’s seminal study Learning From Las Vegas, which also lent a crucial element to my understanding of the highway strip and roadside architecture; buildings that seemed bland, or not worth paying attention to, took on new significance. Contradicting Venturi’s embrace of the “decorated shed,” I was also reading James Howard Kuntsler’s potent tirade against placelessness, and for the sanctity of small-town America — as written in his book The Geography of Nowhere. Later the long-term photo projects by Camillo Vergara looking at inner city America also had a profound impact on me. So accepting the diversity of the man-built environment, while being influenced by divergent viewpoints about that landscape, across different social strata, broadened the range of what I photographed, and took me beyond the visual. I wanted the photographs to be more than photographs. Does all this social theory make the photographs better? I can’t really say. I merely felt better informed about what I was shooting. This information added (for me) a certain urgency, impetus and backbone to what I was up to.

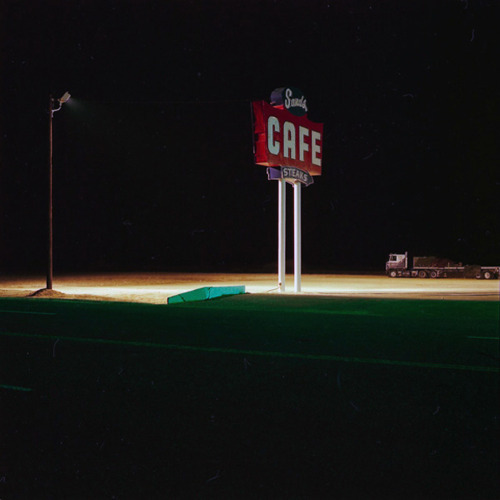

© Jeff Brouws, Vega, Texas 1991

© Jeff Brouws, Croton-on-Hudson, New York 1991

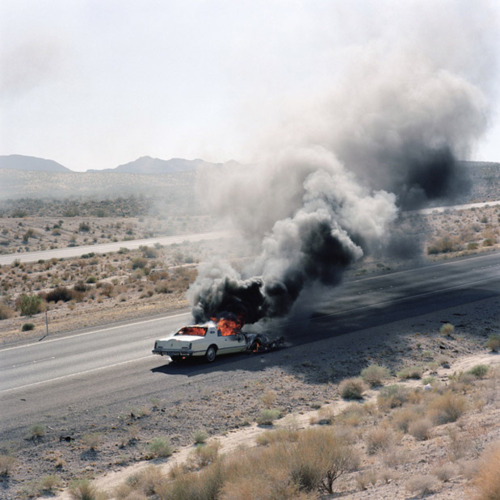

© Jeff Brouws, I-40, Needles, California 1995

© Jeff Brouws, Maricopa, California 1992

Your recent series Discarded Landscape presents a sense of post – cataclysmic imagery where the landscape possesses a deathly silence. I see a connection between this subject matter and your other recent project about nuclear armaments. Is this something you were thinking about?

JB: Not consciously but I do see a connection. I’ve always been interested in the cast off, what cultural geographers call TOADS: temporary, obsolete, abandoned, or derelict sites. The two types of landscape you ask about fit into this category nicely. More than ever that TOAD notion for me gets coupled to history or economic transition; how did cultural or historical progress impact the sites I’m looking at? The nuclear testing sites, by mere virtue of what happened in these places, definitely has a post-cataclysmic or post- apocalyptic feel to them.

Aesthetically-speaking I’m also attracted to minimalism; how does a photographer achieve a certain potency within the image utilizing an economy of means? Something that has great descriptive powers can be stripped down. That might seem counter-intuitive. I think of the spare language and simple words of Raymond Carver’s short stories for instance. They have great emotional resonance without being fancy or over blown. I often seek that kind of visual brevity. Someone once said “the first move to make in a creative act is the one of restraint.” Perhaps, quiet restrained landscapes match the emotional tenor of what I’m trying to impart with these images.

Regarding the inner city environments you’re referencing. One thing that a non-inner city resident is struck by when venturing into those zones is a feeling of being inside a post-apocalyptic landscape. It’s even more chilling when you realize that: first you’re standing in a city in the most affluent country in the world, and second, these are everyday landscapes for 13% of our citizenry, most of whom are minority populations. I can tell one story here. I was down in New Orleans shooting in the Lower Ninth Ward two years after Hurricane Katrina and things were still a mess. A guy comes by in a pick up truck, rolls down his window, and says: “Can you believe we’re in America?” It struck me that that devastated Ninth Ward landscape looked typical to me (and hence familiar) of many inner city environments, especially Detroit, I’d already been in. It wasn’t foreign. To the uninitiated who normally don’t go into (or inhabit) these places… It was a shock. As it was for me the first time I drove through Gary, Indiana, or Detroit in 1999. Yes, it was hard for me “to believe we were in America” but it wasn’t a surprise based on the previous landscapes I’d seen.

© Jeff Brouws, Discarded Landscape #2, Cleared lot in former Central Business District along Broadway, Gary, Indiana 2000

© Jeff Brouws, Discarded Landscape #6, Abandoned Agway grain elevator and industrial yard, Buffalo, New York 2001.

© Jeff Brouws, Discarded Landscape #23, Abandoned manufacturing plant in mixed-use neighborhood, Detroit, MI 2006.

© Jeff Brouws, Discarded Landscape #35, Fire damaged house and backyard along 8-mile Avenue, Detroit, MI 2008.

© Jeff Brouws, Discarded Landscape #16, Abandoned New York Central Railroad Station, Buffalo Central Terminal, Buffalo, NY 2007 (homage to Eve Morgenstern).

Could you describe the relationship between Discarded Landscape andFranchised Landscape?

JB: The growth of sprawl (aka the franchised landscape) has a direct correlation to inner city America (the discarded landscape) and for the most part is responsible for it’s demise. But it’s complicated and multi-faceted. To give you some background: urban development between 1890 and 1930 had been characterized by centralization as Americans’ moved from rural environments into cities. Crowding occurred and this became a factor encouraging decentralization — movement of human beings, materials, capital, and goods away from the city center. Also, prior to the 1930s there was no organized infrastructure of highways across America; unmarked roads and scarce services for the motorist were the norm. As automobile usage exploded in America a cartel of lobbying interests including the oil, tire, automakers, insurance companies, land developers and the Federal Government (with it’s low-interest FHA loans) came to the realization that roads and freeways were a vital component of infrastructure that would help foster suburban development and perhaps jumpstart the country out of the Depression. So began a trend toward suburbanization and the descension of the inner city.

Later after WWII, with the threat of nuclear war a possibility in the early 1950s, Eisenhower and the Federal Government decided that a decentralized populace, not crowded together in urban areas, would stand a better chance of surviving. Thus was born the interstate freeway system that fostered this decentralization, which also conveniently happened to be a natural agent stimulating development, growth and speculation at the urban periphery (suburbanization). Baby-boom families wanting to escape urban crowding opted for a ranch house out on former farmland. Workers would commute into the city to work. Manufacturing firms located in city centers had no room for expansion and started moving to cheaper land (as well as seeking less expensive labor) outside the city. Housing prices plummeted in urban areas as there were more sellers than buyers.

You then see where de-industrialization and white flight start impacting the city environment. Minority populations who couldn’t afford middle-class homes out on the periphery (or we’re excluded intentionally by restrictive racist covenants) opted to stay in the city and overpay for substandard housing offered by unscrupulous real estate agents. Or rent from equally unscrupulous white slumlords who failed to maintain properties because they couldn’t get coverage by insurance companies who red-lined whole neighborhoods as “unsafe bets.” These kinds of discriminatory housing policies also impacted urban environments. A spiraling downward dis-investment continues. Throw in racial tension in the 1950s and 60s, more and more companies and services moving to the suburbs to escape all these problems, and you see that on a “creative destruction” level, suburbia got built on the back of inner city America. Suburbs eventually became cities unto themselves (one could now work, shop and live there); there was no further need to go downtown— a place characterized by a dominate minority population, and a heterogeneous atmosphere that was and is the antithesis of all the homogeneity found in the “safe” suburbs.

© Jeff Brouws, Superstore Under Construction on former farmland, Indiana 2004

© Jeff Brouws, Franchised Landscape #8, Tennessee 1997

How do you prepare yourself for these trips?

JB: As is probably clear from your first question: I do a certain amount of reading and research into subjects I’m photographing. Utilizing Google Earth I also do aerial reconnaissance of areas I’m traveling through (especially if it’s a heavily urbanized area), just to make sure I’m not overlooking something that isn’t obvious on the ground. I also like to “starve” myself a bit photographically and don’t do a lot of shooting prior to going. I want to be excited about picking up the camera. If you’re asking about the style of the trips… early on the cross-country treks were more of a ramble. I had a starting point and a destination and usually took two-to-three weeks to get to where I was going. Sometimes I’d only get 150 miles down the road on any given day if a lot of photography was happening; other times the daily distances covered would be greater. If was all very intuitive. These days I tend to be more focused and drive to specific locations (as I did in 2009 while working on my nuclear project in North Dakota), work for an extended period in that particular area, and then return home. I think more intentionally these days.

The After Trinity series often places us in the vantage point of viewing the forbidden. Were these thoughts with you when you were photographing these sites of nuclear armaments?

JB: Yes. I feel very lucky to have gotten into places like the Nevada Test, the Trinity Site, or the abandoned Nike Missile silo in the Angeles National Forest — not exactly everyday landscapes most Americans have access to. While they definitely feel “off limits,” I was quite surprised how much transparency there was — I simply wrote letters to the appropriate government agencies and was granted access. The remnants found in these locations — decommissioned former weapons systems, or the detritus of early nuclear testing — certainly made them strangely surreal places, but the fact they were also so sequestered and hidden from public view also added to that feeling of forbidden-ness. The active ICBM missile silos that I photographed in North Dakota in 2009 (and earlier in Colorado in 1987) were a real conundrum: they’re in plain site, you can see them from public roads, you can even theoretically stand within 15 feet of their fence perimeters, and yet I’ve never experienced such a feeling of doing something illegal. Even though I had tacit permission from the Air Force to be doing what I was doing.

© Jeff Brouws, Trinity Site 5, perimeter fence at location of first atomic bomb detonation, Alamogordo, New Mexico 1987.

© Jeff Brouws, Trinity Site 1, location of first atomic bomb detonation, Alamogordo, New Mexico 1987.

Your writings are a significant part of your work. Did you ever consider being a journalist?

JB: I did do a little photojournalism work thirty years ago, but found I only enjoyed the writing when it pertained to photographs or a subject that interested me. To be a full-time journalist it’d have to be a “have pen, will travel” scenario, and I never saw myself as just wanting to write for the sake of writing. I’ve only written about my work through necessity — when I was involved in making a book (or contributing to a blog) about a particular series. I felt including language with the visuals would be an enhancement, a way to more fully explain the work and its intentions. I find writing difficult, but in the end, the editing and refining process is intriguing. You can rework text in a way you can’t rework a photograph. When I’m into it I like the process.

---

LINKS

Jeff Brouws (Book Approaching Nowhere available here)

United States

share this page