Tell us about your approach to photography. How did it all start? What made you become a photographer?

Heleen Peeters (HP): In high school I participated in the school’s photo club. Every Wednesday afternoon we discussed images and practiced printing techniques in the darkroom. During the weekends I would go out and make photographs of my friends and my surroundings. I realized I enjoyed working with visual media and decided to study photography more. By the time I was in year three (age fourteen) I switched schools to attend an academy with a full time program on photography. I haven’t stopped studying photography since.

Tell us about your educational path. What was your relationship with photography at that time?

HP: The first four years I studied photography were at a Belgian high school. This course was very technical but formed a good base. At the time analogue photography was still booming, and we had to learn every aspect; printing techniques, photo history, composition studies, and more specialized fields such as optics and photochemistry. After graduation I moved to London to attend a three-year bachelor program at London College of Communication. This course was very different; technique came second, the idea was most important. At first this was very challenging, sometimes it was difficult to explain the meaning and purpose behind your work. Writing and reading about photography helped in this process. In doing so my interest in photography grew, not only as a photographer, but also as an academic. After my diploma I moved to The Netherlands to start a master program in film and photographic studies at the University of Leiden. No practice, just research. Spending time learning about other people’s work was surprisingly inspiring. As a result I don’t see myself only being a photographer because half of my time I participate as a curator or a writer. The diversity keeps me in an inspirational flow and this in turn helps to improve my own practice.

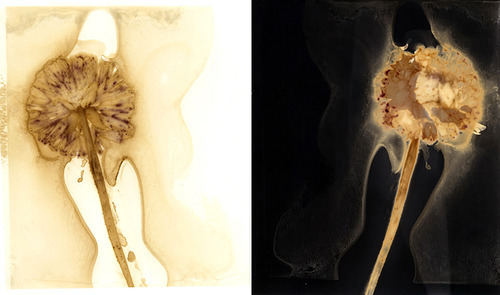

© Heleen Peeters, Hortus Botanicus, Chemigram, 2012

© Heleen Peeters, Hortus Botanicus, Photogram, 2012

What were the courses that you were passionate about and which have remained meaningful for you?

HP: When I was studying in London we had a great visiting speakers program. Once a week artists would come by and talk about their work. Of course not every speaker was as interesting but certain talks were very stimulating. For example, I really enjoyed a visit by Tim Walker. He spent the whole afternoon showing photographs of shoots that terribly failed. He said that there was no point in showing his finished work; it would be impressive but not very productive. By presenting his mistakes he wanted to show us that not every idea works, and that this is ok.

© Heleen Peeters experimenting with liquid emulsion in the darkroom, 2013

How did your research evolve with respect to those early days?

HP: Photography offers the possibility to work very fast. In the beginning I wanted to make “beautiful” photographs. I was trying all kinds of image-making, eager to find out which path to follow. I did not think in series or considered the use of other media. Today I have slowed down and produce long-term in-depth projects. In doing so I often make use of analogue techniques. I am not a scientist and I don’t know exactly how every process works. When developing or printing analogue photographs it feels a little magical. Thereby the process, the path to make a picture of picture, became an integral part of my work.

© Heleen Peeters, Continuum, Unfixed Photo-Emulsion on Concrete Wall, 2013

You use many old analogue techniques such as photograms, chemigrams and coloring photographs by hand. Why do you choose to work with these techniques today? How you choose specific techniques for each project?

HP: Fragments of memories, stories and dreams inspire my projects. I want my photographs to leave room for imagination, where the world of objects transforms into a world of visions. No matter how often I work with analogue techniques, every result feels special; the emergence of form out of formlessness. By highlighting this process, I would like to harness the ephemeral of the moments I portray.

In the text for ‘Continuum’ you wrote “Stopping to pause and look - really look - has become as rare a treat as it was 150 years ago.’’ What do you think about photography in the era of digital technologies and social networking? How you can you make people really look at your works?

HP: The digital era has opened new possibilities but also came with difficulties. The easy-to-use technology has over-saturated the world with images; there are millions of photographs produced everyday and this has an overwhelming effect on the viewer. With the image taking part in every aspect of life, photography today is facing a political challenge. Image-makers therefore need to investigate alternative strategies to stimulate participation from their viewers.

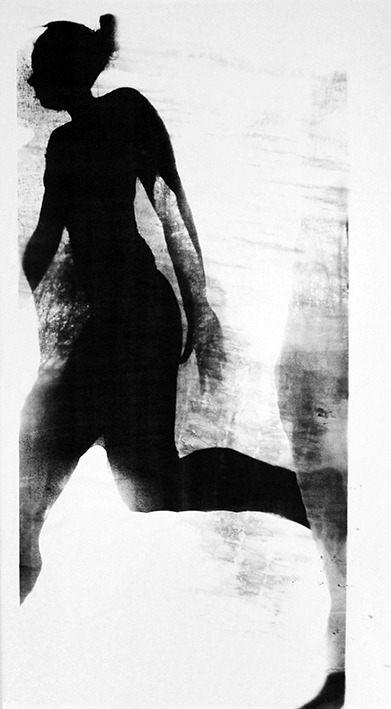

One way I am trying to trigger interest from the audience is by creating flux works such as ’Continuum’ or ’Orpheus & Eurydice’. Both pieces are unique and only visible for a limited time. The longer the work exists, the more it becomes unrecognisable. Quite the opposite from what is happening today: images are available all the time, can be countlessly reproduced and any size is possible. Thereby those who view my work are urged to look carefully, because you never know if you will be able to see it again.

© Heleen Peeters, Orpheus & Eurydice, Unfixed Photogram, 2011

Your work is inspired by fictional stories such as the children’s fable ‘Peter Schlemihl’s Miraculous Story’ and the Greek mythology of Orpheus. What interests you in these stories?

HP: What I like about those two stories is their focus on existentiality. The story on Peter Schlemihl was based on the writer’s biography. Albert von Chamisso was a traveller, he had no fixed home as he was forced to continuously move during the French revolution. His lifelong journey was trying to find a place where he belonged. In the Greek mythology of Orpheus the main character was also adrift. He lost all purpose in life because his love was taken to the underworld. Having moved countries five times in the last ten years I had many moments when I wondered which place to call home. Was home the place I grew up, or the place I live now?

Tell us about the ‘Atlas of Peter Schlemihl’?

HP: The Atlas of Peter Schlemihl is project build out of several photographic series. It is based on a 1814 Children’s fable by Albert von Chamisso. The book titled ‘Peter Schlemihl Miraculous Story’ tells the tale of a man who sells his shadow to the devil. Though rewarded with a bottomless wallet, Schlemihl quickly discovers that without his shadow he is rejected by society. The woman he loves rejects him, and he himself becomes involved in guilt. After a long period of grief and exclusion, Schlemihl escapes into nature searching for the peace of mind that was bartered away. With the aid of his seven-league boots, he travels the world studying everything concerned with fauna and flora. In the end, he finds communion with his own better self and dies a satisfied man. Together with Japanese artist Masayo Matsuda, I made an “atlas” on our interpretations of this story. By doing so we wanted the viewer to travel from real to imaginary spaces, exploring the boundaries between autobiography and fiction. For example, the series Untitled (Utopia) is a series that belongs to the Atlas of Peter Schlemihl. In the story Peter Schlemihl travelled the world to scientifically study the earth and to find deeper truth about himself. The series “Utopia” visualizes the beginning of Peter Schlemihl’s journey. The paradise-like black and white photographs are hand coloured with paint. This action symbolizes the colours that grew back in front of Peter Schlemihl his eyes after a long phase of darkness and negativity.

© Heleen Peeters, Untitled (Utopia), Hand Coloured Black and White Photograph, 2014

You investigate one theme by combining several series. How did you develop this way of working?

HP: In 1816 when Nicéphore Niépce invented the medium of photography, he described it as ‘artificial eyes’ in a letter to his brother Claude. If Niépce explained his invention as making ‘artificial eyes’, how should we describe vision through our own eyes? Maybe everything that is seen through light could be called ‘photography’? The camera is a tool that stands in relationship to the eye. The eye stands in connection with every viewer’s intellectual experience. The result is that every perceived optical phenomenon by means of intellectual association transforms into a personal conceptual image. Essentially this describes ‘vision’ in the broadest sense of the word. I like the kind of photography that takes this stand into consideration. These works question the function of the image and the construction of subjectivity in our contemporary culture. By creating multiple voices, you let go of control. Nothing is linear, lines crisscross, coincide and change direction. The viewer has the freedom to decide the rhythm and the form in which the work develops.

© Heleen Peeters, Alchemist Chemigrams, Chemigram, 2014

Is there any contemporary artist or photographer that influenced you?

HP: There have been numerous artists that inspire my work. The following three works have been of value in discovering my own work.

- Photo book: Esther Teichmann: SPBH Book Club Vol V.

- Light installation: Shylight by Studio Drift.

- Picture book: Albertus Seba, Cabinet of Natural Curiosities.

Is there any show you’ve seen recently that you find inspiring?

HP: In the summer I saw the exhibition Love Radio by Eefje Blankevoort and Anoek Steketee at Foam. The work, which has been presented on different platforms (web documentary, mobile app, publication, exhibition), depicts Rwanda twenty years after the genocide. By layering their topic with different voices they make clear that the truth does not exist, there are solely different perspectives on the truth.

Projects that you are working on and plans for the future?

HP: I have several plans ready for the future, among which:

- I am making a new website to showcase my work.

- I began a new project last summer in Japan; the first pictures will be released soon!

- I am producing a new series that is part of The Atlas of Peter Schlemihl. For this work I am experimenting with printing an image on a mirror.

- I am creating a video piece that is part of the project Hortus Botanicus. It will be the first time I use moving images, scary but exciting.

---

LINKS

Heleen Peeters

The Netherlands

share this page