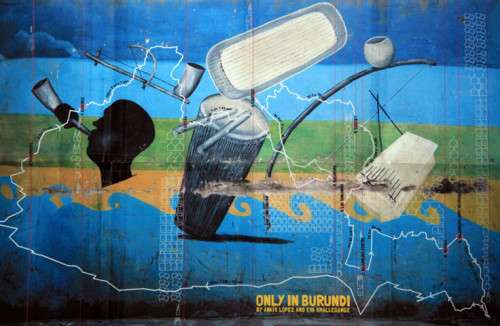

© Anais Lopez from the series ‘Only in Burundi’

Anais Lopez (AL): Let’s start with a beautiful picture. I am fortunate to have this postcard you sent me years ago on my bookshelf. Sometimes I fall on it, I like the intimate feeling and its silence. Tell us about this photo?

On this picture you see Ella (13), she is the daughter of our friend and guide Koky, the main character of the book. I took the picture at six in the morning, Ella is standing there in her pj’s looking at the outside world. She didn’t notice me at all. If she had, she wouldn’t have let me take the picture without doing her hair and dress properly.

© Anais Lopez from the series ‘Only in Burundi’

AL: ‘Only in Burundi’ it is a wonderful journey of discovery of Burundi. As you read and browse the stories and images that make up this beautiful book you slowly approach the country. The figure of Koky is very empathic, almost fictional, a sort of master key that guided you on this journey. How Koky has influenced your work? And what could it be this without him?

Without Koky, there wouldn’t have been a book. Like you said he is the key to the whole story. Koky’s explanation on how the society in Burundi works, what you need to survive there (without the right connections you are nowhere) and how you find a place in society was crucial for this project. Koky influenced me in that I wasn’t looking for the perfect picture anymore, I was much more interested in taking the reader on a journey using symbols and photography as a tool and not as an aesthetic end result.

© Anais Lopez from the series ‘Only in Burundi’

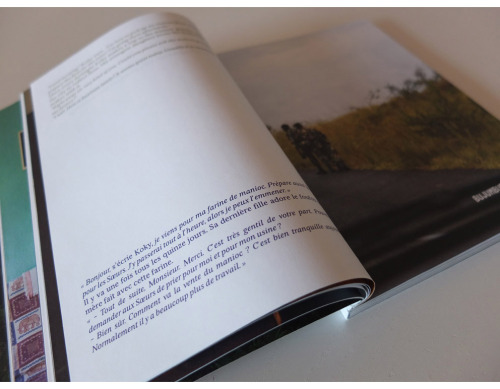

AL: Talking again about 'Only in Burundi’ I find interesting the graphic layout, but also the balance that you reached between words and images. Reading is smooth, phtographs are necessary pause and help to structure a visual imagery. One has the impression of browsing a travel diary. This makes it all exciting and less cerebral. What brought you to this narrative approach?

Both trips Eva Smallegange (writer) and I made felt like an unbelievable journey. Once home when we sat down with Linda Braber we decided it should be a travel book. We wanted to show a new Burundi, not only to my fellow colleagues but to the whole world. We wanted to interest people in how this little country worked. So we came up with the idea to use a different narrative approach and make it a travel diary. We realize pretty soon that it worked. Most of our readers are global citizens who work or worked in Africa. We got these amazing letters that they finally understood how the system works, how important it is to have the right connections and know-how to use them to get things done there and find your own place.

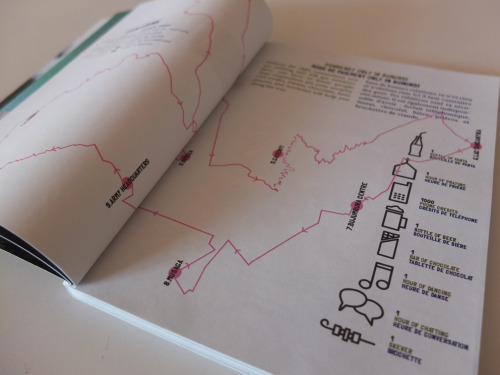

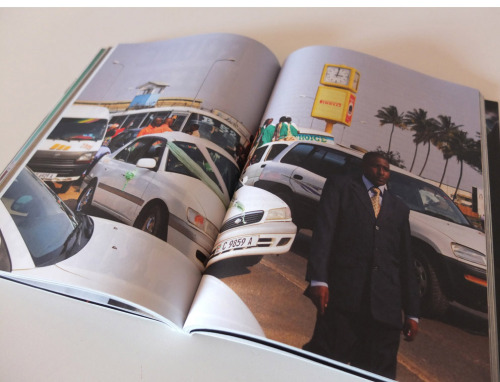

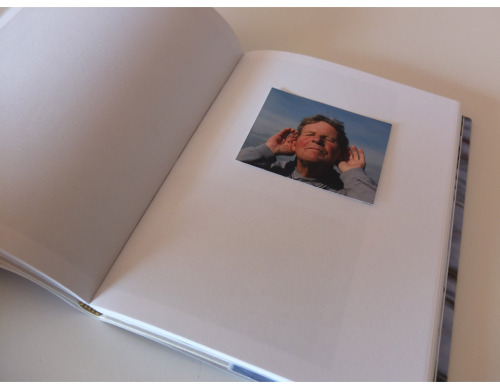

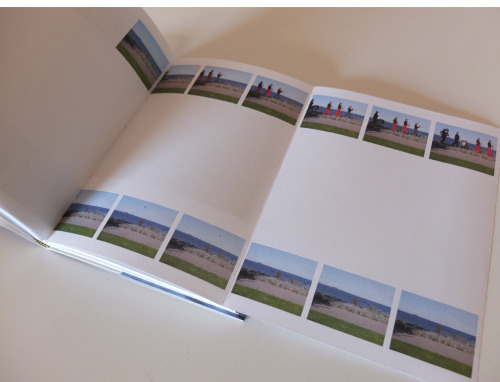

Still images of the book 'Only in Burundi’

AL: Let’s talk about your photography. How did all started? What are the memories of your first shots?

Since I can remember I wanted to be a photographer and an adventurer. Before going to the Art Academy I wanted to be a war photographer and change the world with images. At the age of 18 I travelled by myself to Central America and started to photograph injustice. Those were my first real pictures. I was quite naive and it almost cost me my life. When I came home I realized I didn’t want to be in the frontlines. Two years later I went to the Art Academy and learned I could use photography in a different way, without having to risk my life.

© Anais Lopez from the series ‘Mika 17’, 2007

AL: Did you had any formal education in photography? Any book, teacher, film that helped to shape your perspective?

Yes I did my bachelor at the Royal Art Academy in The Hague and graduated in 2006. From 2008 until 2010 I did a two year master at the Sint Joost Academy in Breda.

There are two photographers that influenced me a lot. The first one was Koen Wessing, an amazing Dutch documentary photographer who travelled the globe and changed history with his pictures. When I came back from Guatemala I asked him if I could tag along with him and learn about his practice. He convinced me to go to the art academy, he told me being a photographer is a really lonely job, the friends you make at the art academy are going to be your family later. I was quite reluctant to go at first. We made a deal that if I would get kicked out of the academy I could go with him to China. I applied at the Royal Art Academy and Koen was right, in a few months the place became my home and the students and teachers my second family. I stayed for the whole 4 years.

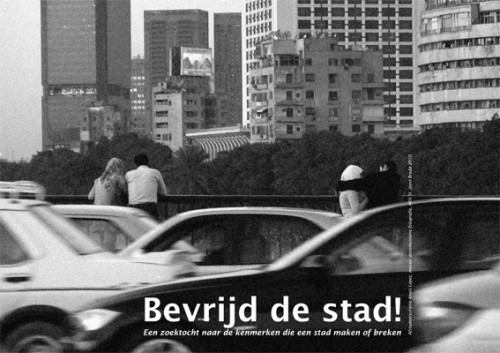

© Anais Lopez from the series ‘Liberate the city’, 2010

When I was studying I came in contact with the work of Raymond Depardon, a French photographer and filmmaker. I was immediately drawn to his work and the way he does it. After working for years as a photojournalist he started to do his own long documentary projects. His later work is a great source of inspiration, not only the work itself but the way he works as well. Like me he isn’t led by the issues of the day but makes documentaries about long lasting societal issues like the changes in the countryside and the fast growth of cities. The way he uses his own voice in his narrative was an eye opener for me on how to engage people and tell a story.

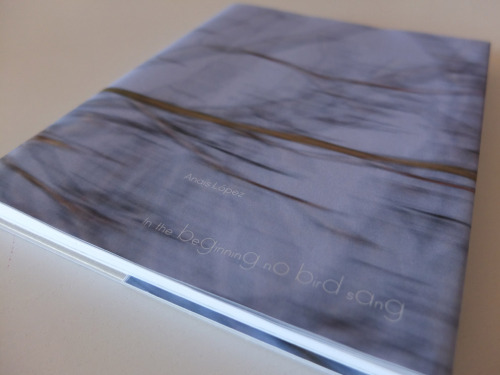

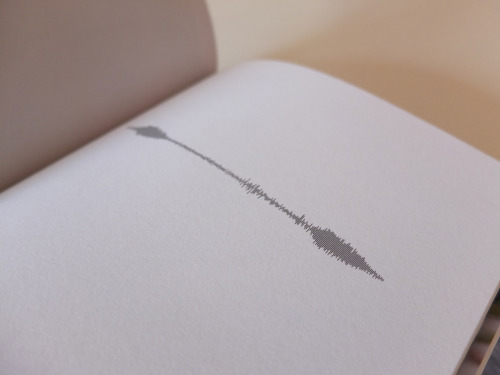

'In the beginning no bird sang’ is another editorial project from you. A pretty sensorial experience. Tell us about it.

‘In the beginning no bird sang’ is a project about IJburg, a new suburb of Amsterdam built ten years ago. It’s the end of the world according to the inhabitants of Amsterdam, because nothing happens there. I was triggered by this place and wanted to know how it is for the inhabitants to live in a city without history. On my search I met Jean, a blind man of 66. He was the first person to approach me on the street. After a short conversation he invited me to go on a walk with him. He lives in block 3b and walks the island every day with his seeing-eye dog. During our walks I discovered that Jean has a special gift; he recognizes almost all the birds on IJburg and can find his way around based on their specific sounds. Jean taught me to stop using my eyes and listen to his city. He showed me his IJburg: an IJburg full of animals, nature and other special occurrences. I photographed the island through his ‘eyes’: the places he visits and the birds he ‘sees’.The project consists of a publication, a photo and video installation in the form of a show box and a sound installation. For exhibition purposes I translated the book into a show box that contains various images from the book and two videos. You can also listen to the calls of the birds through headphones. The sound installation was made by the Dutch audiographer Hannes Wallrafen. Based on several trips Hannes Wallrafen made around the island with Jean, he has created a special soundscape of Jean’s IJburg, that’s presented in a darkened room.

Now you have recently launched a crowd funding campaign ‘Country without orphans’ to support a new project in Rwanda. This initiative aims to support the education of kids and young people after the government decision of closing down all orphanages. Behind your work I read a positive confidence in rediscovering a social responsibility of art. Can you briefly describe this project?

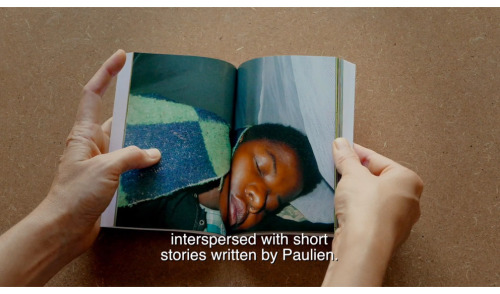

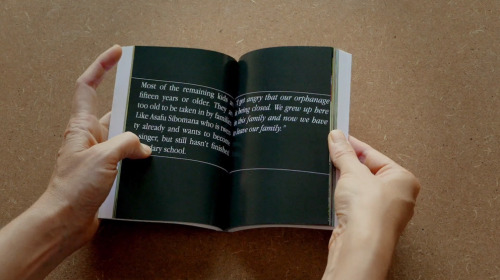

This project has two sides. Our main question was: What happens if a country suddenly closes all its orphanages? Where are the most vulnerable children going to end up? A few weeks before L'Esperance Children’s Village in Rwanda shut its doors, we (filmmaker Anisleidy Martínez, writer Paulien Bakker and me) decided to go to Rwanda and visit this last orphanage. We wanted to investigate. We gave a photography course to the 32 remaining children. The orphanage is located on the edge of Lake Kivu, bordering Congo. There is no electricity, no tap water, and there are no mirrors. With camera in hand, the children learned to look at themselves and their world. They photographed their brothers and sisters before they were sent to live miles away from each other. Once we got back to the Netherlands Holland, we couldn’t just leave them to their fate. We had a collection of amazing images so we came up with this crazy idea: let’s make a beautiful photo notebook with their pictures, and sell them so we can help them to school. Our goal is to raise as much money as we can to send as many orphans as possible to school. That is the first part of our project.

Besides helping them we are also making an artistic project. In June 2015 we went back to follow the lives of five children after they left the orphanage. The children continued photographing and filming their own lives. Hirwa (13) and Jean-Cloude (11), the main characters of the story we are making, now live in a tiny house in Kigali with their mother, 26-year-old Fareeda, who is a woman of the night. The promised financial aid didn’t get past the priest, who is a merchant who one day decided to start his own church. This second part of the project is where we want to tell the bigger story about the difficulties with finding a place in a society where you were not welcome from the start. It’s about acceptation and finding a place where you belong.

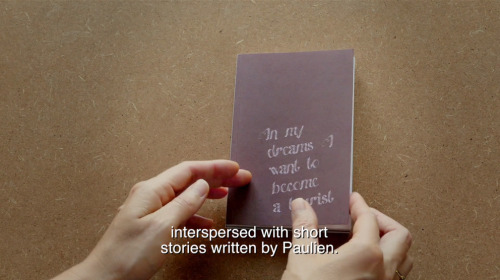

Still images of the book ‘In my dream I want to become a tourist’ from the video of the crowd funding campaign ‘Help us send Rwandan orphans to school’. The book is selling to support the goal of educating at least 5 kids through secondary school. Read more from HERE.

In your vision what is the role of photography, and how do you see its future in a time dominated by simulations? Should we foster a higher human empathy in our actions and practices? As you state in your website «The main question I ask myself in my work is whether people make the city or the city makes the people»…

My aim is to get my photo stories to the widest public possible. By moving stories forward we can make people care on so many different levels. It all starts with you telling your story to different audiences.

I do think we are living in a time where people need (photo) stories to make them dream, make them care and get them acting. Does it always has to go hand in hand with a campaign for a good cause? No, I think the most important thing is that we continue to make our stories no matter what and that use all the tools we have to spread it and inspire people: to make them think and get them engaged.

And sometimes a story comes along, like in the case of these orphans, where it just isn’t enough to tell the world about it and you feel the need to do something right now. That is when you become an activist.

---

LINKS

Anais Lopez

The Netherlands

share this page